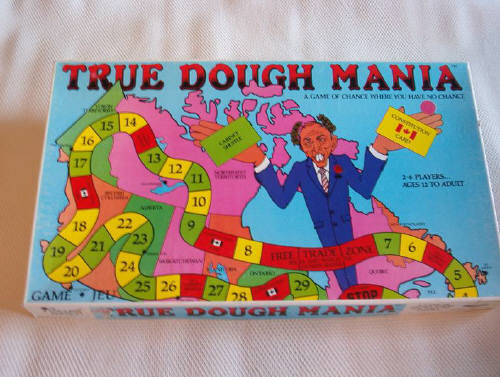

Jeff Rubin, chief economist at CIBC, has been said to be half entertainer, half economist. What I was personally told is, “He's a walking circus.” Given the partial transcript of The Toronto CFA Society's annual forecasting dinner, I conclude that he at least has color.

The National Post says, “Here is a transcript of the highlights, edited for space and to remove jibes and insults.” No jibes?!! Bullocks, daddio. I did a search for jibes, ludity etc etc, to no avail. The transcript may be clean, but it's still an interesting read.

The speakers quoted below are Ralph Acampora, managing director of Knight Equity Markets in New Jersey; Bruce Campbell, chief executive and chief investment officer of Pyrford International PLC in London; Jeff Rubin, chief economist and strategist at CIBC WM.

Q: On the general direction for the stock market?

Acampora: I think in the next 12 months it's going to be a major rotational theme. I think commodities in general peaked a while ago. I think they're going to be under pressure, money comes out of those sectors of the market and goes into things like large-cap blue-chip stocks: healthcare, technology, telecommunications, stocks like At&T.

Campbell: Down.

Rubin: There's only two issues out there. Is the U.S. housing market going to have contagion effects ... and the second issue is, if the U.S. economy does blow up, is it going to bring down the global economy and by implication commodity prices and I would argue the Fed is going to do whatever it takes to limit the contagion effect and the U.S. economy, unlike the 1990s is no longer driving the global economic bus and sure as hell isn't driving the global economy.

Q: Biggest contrarian call for 12 months' time?

Campbell: Gold at US$999, if not sooner.

Rubin: Oil will set new record highs in

2007.

Acampora: Crude has a very sharp decline that most people are not expecting ... to US$40-US$45.

Q: Speaking of oil?

Rubin: Reality is yes, we are getting new increases in supply but when we're drilling 35,000 feet in the Gulf of Mexico or we're schlepping a tonne of sand to get a barrel of oil the supply curve is a little bit different. I think we're going to see oil prices continue to rise. The only obstacle in the face of higher oil prices is a global recession, and I don't see that on the horizon.

Campbell: Despite having a sneaking regard for what Jeff said, I'm not bullish on the price of oil at all in the next 12 months. A significant U.S. recession might be reasonable odds on. If there's a significant U.S. recession it will take three or four million barrels off the table, but if we don't see a significant U.S. recession we could easily see the price of oil back at US$70.

Acampora: I believe equities lead the commodities and I want to challenge anybody to answer why are most drilling stocks reaching monthly lows, multi-lows and large oil companies like Conoco-Phillips breaking down in price? I think it's a harbinger, at least on a short-term basis, at least for six months, there will be pressure on crude.

Q: On metals?

Campbell: Unlike oil, I can't see any reason at all for metal prices in aggregate to rise. There's been far too much leverage and speculation in the metals and it's unwinding.

Rubin: When you look ... China is 160% of world copper consumption ...

Acampora: Jeff everybody knows that.

Rubin: You Americans think it's all about [you] but that's BS because exports to the U.S. from China are the grand total of 8% of its GDP. Last year China produced 6.5 million motor vehicles, not one single motor vehicle was exported to the United States. What we have here is that we are guilty of a very Americentric view of the world. We think that China's rapid growth of 10-12% is all about supplying customers in Little Rock, Arkansas. And that just ain't where it's at. It's not trade-linked to the U.S.; it's exploding domestic demand.

Acampora (deadpan): If it wasn't for the U.S. consumer, the world would stop.

I have to step in and say that Rubin has lost me here. I don't think it's any secret that trade between China and the U.S. is unbalanced. There's nothing “Americentric” about the fact that U.S. consumption is monstrous. Moving on...

Q: If there's so many risks out there, including the U.S. current account deficit and housing, why are stocks going up?

Campbell: Well, they shouldn't be should they? Stocks are actually overvalued.

Rubin: What you talk about as value investing, I regard as fluff. Last year, the energy index was up 61% and if you were overweight energy you beat the market and if you were underweight energy you lost to the market. I wasn't in favour of energy stocks because of the management at Imperial Oil or Canadian oil sands or Suncor. Management is irrelevant. I look at commodities. You get the commodities price right you can have all kinds of management. As far as the long run versus the short run, I think Lord Keynes had the best comment about the long run -- in the long run we're all dead. The long run is a continuum of short runs, you get the short runs right the long runs will look after

themselves.

Q: Worried about hedge funds?

Campbell: It is a concern to us. Our office is in hedge fund alley, Mayfair London, where they open a 100 a week and close a 100 a week. If you ever want cheap furniture you just wander around the streets. There's a lot of stuff going on ... that we can't quantify and there will be some major financial accidents in the next few years ... and it will be tough to bail out the financial system when it happens.

Q: Best money-making idea for the next year?

Acampora: Oracle, AT&T, Qwest, Baxter Healthcare.

Campbell: Boring old large caps. A gold-mining stock in Australia called Newcrest.

Rubin: I believe uranium oxide will be at US$70 per pound and if certain companies would stop hedging the next 200 years of production I might make some money. But I think we are looking at a renaissance of nuclear power around the world. No. 2 would be oil if you can separate natural gas from oil (Suncor, Canadian Oil Sands.) and the financial sector [on expectations of interest rate cuts].