Productivity and firm size in construction, pt2

A couple of posts back I asked why Canada’s construction sector is said to be more productive than the U.S. sector, despite having smaller establishment sizes. The gap isn’t huge, but it’s surprising. I don’t know if any single concept can answer this. Instead, I’ve broken it down to two questions: why are the Canadian firms small, and why are they more productive.

On being small…

Small establishments are unburdened from taxes on inventory

If one considers the high taxes that the construction sector faces on inventory, it seems reasonable that large companies wish to unburden themselves of this tax by contracting individuals to do certain services. Perhaps in Canada self employed contractors are more willing to take on the risk of being taxed on inventory (perhaps due to favourable tax scheme on Canada’s self employed, in comparison to the U.S.? I don’t know if this would justify the gap).

If one considers the high taxes that the construction sector faces on inventory, it seems reasonable that large companies wish to unburden themselves of this tax by contracting individuals to do certain services. Perhaps in Canada self employed contractors are more willing to take on the risk of being taxed on inventory (perhaps due to favourable tax scheme on Canada’s self employed, in comparison to the U.S.? I don’t know if this would justify the gap).

Variable taxes, in contrast to flat taxes, keep establishments small, even in Canada’s most populated areas where construction productivity is destined to be highest regardless of establishment size

B.C. has the lowest provincial tax rate in Canada up to a taxable income of $67,500 per annum. Above this income level, the rate rises rapidly and Alberta becomes the lowest personal tax jurisdiction at an income of $88,000 per annum. B.C. has the highest unincorporated self employment rate of all of Canada in the construction sector while Alberta has the highest incorporated self employment rate (see graphics below that I created using StatsCan CANSIM data Table282-0011). Perhaps Canadians are more sensitive to an un-level tax scheme than Americans.

Here's my colour scheme: B.C. has the lowest provincial tax rate in Canada up to a taxable income of $67,500 per annum. Above this income level, the rate rises rapidly and Alberta becomes the lowest personal tax jurisdiction at an income of $88,000 per annum. B.C. has the highest unincorporated self employment rate of all of Canada in the construction sector while Alberta has the highest incorporated self employment rate (see graphics below that I created using StatsCan CANSIM data Table282-0011). Perhaps Canadians are more sensitive to an un-level tax scheme than Americans.

self employed unincorporated w/ no paid help,

self employed incorporated w/ paid help,

self employed incorporated w/ no paid help,

and the final pie in lime is self employed unincorporated with paid help.

On being more productive…

Economies of scale are relatively unimportant in the construction sector

Construction is highly labour-intensive, depends on a high proportion of low-skilled jobs and is not considered a high technology sector. Further, I would argue that where economies of scale do matter in the construction sector, they mean less than they once did. Thus, simply being big doesn’t give U.S. firms a greater advantage in this sector.

Construction is highly labour-intensive, depends on a high proportion of low-skilled jobs and is not considered a high technology sector. Further, I would argue that where economies of scale do matter in the construction sector, they mean less than they once did. Thus, simply being big doesn’t give U.S. firms a greater advantage in this sector.

And yet this isn’t the case with other labour intensive industries. The U.S./Canada "productivity gap is large in other labour intensive industries such as textiles and clothing as well as in fabricated metals, the machinery and computers industry, and the electronic and electrical equipment industry." So maybe this idea is a dud.

The hidden economy

If labour inputs are somehow being underestimated, then productivity (measured in my last post as GDP divided by hours worked, by the way) could be distorted.

If labour inputs are somehow being underestimated, then productivity (measured in my last post as GDP divided by hours worked, by the way) could be distorted.

For example, John O’Grady (2001) estimated that, on average, the annual underground income in Ontario’s construction industry, in the period 1998-2000 increased to $2.395 billion. This is due to the "hidden economy" composed of self-employed individuals who wish to conceal their income, which we know is easier to do in the construction sector than nearly any other sector.

Also, I think dachisb made a good point in response to my first post: "I would wager that low cost labour (read mexican migrants) drives most of this difference."

Not all construction is made equal

I’m not sure what affect this would have, but I thought it was worth noting that heavy and civil engineer construction is much smaller in Canada then, say, the construction of buildings. Surely many modes of construction have their own unique productivity level, and the compilation differs across countries.

I’m not sure what affect this would have, but I thought it was worth noting that heavy and civil engineer construction is much smaller in Canada then, say, the construction of buildings. Surely many modes of construction have their own unique productivity level, and the compilation differs across countries.

Am I missing anything? Any more ideas anyone?

9 comments:

Construction in the US is one of the last remnants of heavy unionism. In the US anyway, unions have a reputation of heavy overstaffing, at least in the popular imagination. Construction is easy to eyeball as an outsider and simply see many people apparently doing nothing at any given time.

In fact, looking at your chart from a post or two ago, construction, transportation and mining are quite unionized, especially compared to the rest of the US economy. Maybe it is simply a case of Canada having unions in more sectors than the US in general, and those sectors that the US also has unionization the gap closes, with the gap being large in US non-unionized sectors. With construction seeming to stand out, perhaps Canada's construction unions manage to get away with less overstaffing than the US, especially if the US has a higher percentage of construction on government owned and financed projects, like the infamous massive cost-overrun Big Dig in Boston.

It is not just in my mind that unionization in the US takes a toll on productivity, The Economist "Newspaper" seems to believe the same, at least in airlines anyway. To quote from the linked article:

A team of aviation consultants from America, who turned round Continental Airlines in the mid-1990s, tried to fix Alitalia but were defeated by the intransigence of its workers, who surpass even America's notorious aviation unions in their determination to defend overmanning and economic privileges

Maybe we can discuss the issue of productivity and why it is considered a good thing, versus the tenacity of unions to cling to "overmanning and economic privileges", as suggested above. Productivity is beneficial to the capitalist by maximizing his benefit while minimizing his cost. But the worker derives no particular benefit other than the employer continuing in business, so that the worker continues to receive a paycheque.

So with a big construction firm, which gains business because of size and reputation (they can take on the larger jobs that a small contractor simply cannot handle), the incentive for the worker to accept lower wages or fewer benefits ceases to exist. The unions are simply being a happy part of the capitalist enterprise.

From the perspective of the worker, the higher wages are higher productivity: he has been more productive, in that he has received more money for the same amount of work.

We can have legislation that protects unions or fights them, that protects jobs or protects capital, or some kind of balance between. It is a mistake to see productivity in such narrow terms, making the assumption that the interests of corporations is identical to the interests of their employees. This is not exactly a zero-sum thing, but it's closer to zero-sum than is usually admitted.

That's one more black mark against most of the economists' assessments, but not the only one. Pretty nearly all the problems are the result of not taking into account irrational behaviours, but this one is the result of not taking into account one wholly rational set of behaviours.

HJ: According to the U.S. Current Population Survey, union membership in construction stood at 13.1% in 2005 (not including collective agreements) Further, the union wage premium for U.S. construction is also relatively large.

By comparison, Canada’s union rate in construction in the same year was slightly over 30 per cent, relatively small for Canada. I get your point. Actually, I think these two graphics help show that your theory would hold well:

The occupations aren’t directly comparable but these give a rough idea.

US (2005) http://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2006/jan/wk4/art02.htm

Canada (2005) http://www.statcan.ca/english/freepub/75-001-XIE/comm/2-2.gif

And thanks for mentioning Boston’s Big Dig project.

Amphimacer: I would agree that different measures of productivity are instructive in measuring different things. GDP/hours worked is probably a better measurement of standard of living than GDP/worker (as Don Drummond explains well here: http://www.td.com/economics/topic/el1005_prod.pdf).

The more stuff that we can be produced in an hour, the more productive we are.

But you say, “from the perspective of the worker, the higher wages are higher productivity: he has been more productive, in that he has received more money for the same amount of work.”

By that definition, every worker would jump to be “productive,” but then half of them would get laid off because the wages are too artificially high for employees to afford. How productive is that?

But perhaps you might have a case using the example of China. As the country becomes more and more productive, there seems to be two effects happening. First, firms are offering increased wages to employees. When China was the land of sweat shops, many people argued that it was simply the case that the objectives of the employers were not the objectives of the employees and therefore low wages were the result. I’m not denying that workers rights were violated in some cases over the same period, but my point is that the firms could not always afford to pay a seamstress what an American firm was paying. Now we see that wages in China are increasing. Increased productivity isn’t only good for capitalists.

Second, increased productivity has been linked to a sharp drop in manufacturing jobs in China. Some people argue (link below) that labour intensive activities are China’s speciality, so it should concentrate on expanding labour inputs and not increasing productivity. It seems backwards. I mean, Canada once specialized in beaver pelts. But we've moved on to more productive things and we're a better society because of it. Back to China...I'll admit that I don’t really know enough to comment.

http://www.rieti.go.jp/en/china/02083001.html

Over the long haul wages track productivity rather closely. To increase the wages of societies members in general, as opposed to a select few who can manage to extract rents via union coercion and government regulations, then productivity increases are key to rising wages.

No amount of chanting "Union Yes!" can change either the paramount importance of productivity or the fact that productivity tracks wages over time. Truedough is correct that wages that are artificially higher than market wages produce unemployment. How productive are the unemployed?

China's wages are going up due to supply and demand. :o In effect, in the locations that both private and public infrastructure are located (roads, ports, factories etc., and mostly in coastal areas near ports) have "run out" of workers and have a labor shortage. A shortage for anything means prices go up. Hence rising prices for labor in China as their wages get bid up. If this eats too much into owners' profits, they have to figure out how to increase productivity via captial investments in machinery or in human capital investments in training unskilled workers. Or close the factory eventually as workers are more efficiently allocated via the market to jobs were they are more productive.

Closing factories because labor has been organically raised via competitive bidding is not unemployment inducing however, except for brief periods since those unemployed workers by definition quikly get bid for again. Contrast this with articifial (i.e. union or government "protections") raises for workers which induce unemployment when marginal factories get closed due to costs that are too high.

Why has China, at least in the locations where it has "enough" infrastructure, "run out" of workers? It does after all have a billion plus people. The answer is it allowed its comparitve advantages to work and the government got out of the way enough since 1978 for investors to create jobs they could profit from. Profit is not a four letter word. The absence of profits means an absence of jobs. Profits that are "too big" get arbitraged away when new investors spot the opportunity and enter the market. This is what has happened as the world has offshored.

Viet Nam looks to be next as Chinese manufacturers move both inland into China and outward into Viet Nam (westerners too, such as Intel). If India's government with its ingrained anti-profit attitude ever gets its act together in something besides IT and outsourcing brain dead back office work, then it too ought to have massively lower poverty rates as workers there get bid for too.

Well said.

Profit is a six-letter word, hj0. Although I was an English major, I also studied accounting and took statistics and calculus in university. But the humanist courses in the curriculum teach you other things, which statistics don't.

No one is a statistic. As a group, we comprise statistical elements, but my wages and yours are not a simple function of how much our employers can pay, or how much we can squeeze out of the economic system. So this whole business of productivity and wages going hand in hand is irrelevant to the worker who has been squeezed out of a job by globalization. My own case, which is of a Canadian job augmented by globalization, doesn't make someone else's situation better or worse.

So instead of looking at it from a pure statistical point of view, try looking at it from the point of view of those union workers: while the company can afford to pay them high wages, they have the right to fight for high wages. When that becomes a problem for the company, how much worse off are the workers for having insisted on high wages and good benefits?

If a worker earned ten to twenty per cent more each year over the fifteen or twenty years he worked for this company, and invested his surplus wages wisely, he is now in a position to laugh at the plant closure. He has enough set aside that he can afford to take a worse job, and still be better off overall, or if he is older, to retire early. Of course, not all the workers who profited by this will have had the foresight to manage thus, but they had the chance, and that's what is important.

This isn't an anti-profit attitude at all. You business-oriented jokers make me laugh. It's a pro-business attitude. Indeed, it's a business attitude. It's entrepreneurial, it's capitalist, and it's perfectly sane and sound.

India isn't an example of anything like labour relations between unions and corporations. It's a huge, unwieldy place without a real history before 1946. Before that, it was a British fiefdom, made up of a group of only loosely connected little kingdoms. That's why it got conquered over and over. Until it became a country, it was not a single big country but a huge bunch of small, poor countries. No amount of government aggression is going to solve the ethnic conflicts that will keep it down, like Yugoslavia or Iraq, two other places that were cobbled together foolishly.

Time will change this, as it changes everything. To get back to what I was speaking of before, one of the things time changes is which companies are successful. That's why there is little real incentive for workers to tie their fortunes to those of the companies they work for, but rather to take as much as they can.

This is capitalism, boys and girls, not bleeding-heart liberalism, unionism gone wild, or any other sort of anti-business, "socialistic" rant. Yes, I do believe in social justice, I believe that we have coddled big capital for far too long. I think we have a responsibility to each other. But I don't think we should outlaw capitalism, only allow that its practice is for everyone, not just for those who start with more money.

That's equal opportunity, something capitalists are supposed to believe in.

This comment won’t address all of your criticisms, but we’ll just have to agree to disagree. I just want to note that the firms vs union argument no longer has much to stand on. Workers today have better tools at their disposal than unionization. On an ordinal scale of things that benefit individuals (ie labourers, entrepreneurs…), unionization ranks below factors that offer benefits to individuals that actually exceed costs, in my opinion. For example, I would rank unionization below labour mobility.

Freedom of mobility creates a mechanism (in today’s free market) where low wages cause workers to switch trades, relocate, or work for the competition. Eg) When wages in the Maritimes fell below workers’ reservation wage, thousands of residents packed up and MOVED west (I’ll admit it, it shocked me). What did Maritime firms do? They imported MOBILE Russians and offered them a higher wage relative to what they had been receiving back home.

Guess what impedes mobility? Government regulations, subsidized industries in deserted and densely populated regions, and….wait for it….UNIONS! Go back to our example of the Maritimes and imagine if a union had successfully inflated wages above where the market clears. (More) unemployment would have (most certainly) resulted. Instead, these workers gained through the freedom of mobility. Actually, so did the Maritime firms, and the Russian factory workers, and the economy as a whole.

Do unions care about I) a firm’s ability to remain competitive, or II) the employees who have been employed, say, less than five years? They do not. Their objectives are to collect dues and bargain for larger wages for the higher-up employees. And when wages increase, firms have no choice but to give the lesser experienced employees the boot; they’re no longer affordable. Unions impede mobility, they prevent firms from replacing labour with capital (eg staffing requirements), impede productivity (thus putting downward pressure on REAL wages in the long run, all else being equal), and cause unemployment. Also, studies show that unionization increases the probability that workers apply for government benefits.

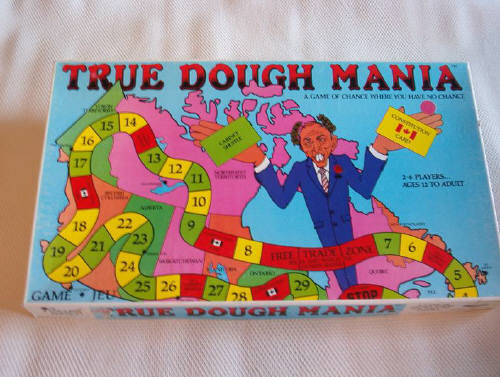

Sorry to rant. True dough has had a long morning and her store bought coffee has a floaty in it.

Mobility is an important tool, of course, but unions can have a constructive role to play. Look at the auto sector in Ontario right now, where the union and the companies are sitting together at the table with the province, trying to find ways to keep jobs, and keep plants open. This involves encouraging the government to provide incentives for local assembly, but it also includes training initiatives, and other bits and pieces. Not all of these will cost the taxpayer money (though, naturally, some will). I repeat, the demand for high wages is made when the company can afford it, and when it can't, the union can help with finding ways to ease the shocks of a bad economy. That not all unions do this doesn't make unionization the problem. Remember that before the rise of the unions, in the latter part of the Great Depression, workers were at the mercy of merciless employers, who were aided and abetted by governments all too willing to beat them up, literally. It was bad, and mere mobility would not have fixed the problem. Balance is the key, as with any system. I tend to lean towards the workers because I am suspicious of people with so much money that they don't understand what it's like not to have it. I've seen way too much of that. You can read about the rise of the unions in a lot of places (I recommend in particular my mother's M.A. thesis (McGill University, 1946 I think) on the rise of the Catholic trade unions in Quebec -- sheer bias on my part, of course). They all show the same thing: an imbalance that needed correcting. Since the North American unions have suffered multiple setbacks in recent years, the balance has shifted back to employers, except when economies overheat (Alberta right now, for example). Even then, rich people aren't the ones suffering the most from the overheating, are they?

Post a Comment