Can a central bank be too transparent?

As argued by Stiglitz (1999)....the information economics literature supports the notion that better information will improve resource allocation and efficiency in an economy. Disclosure of financial information directs capital to its most productive uses, leading to efficiency and growth.

Australia's outgoing central bank governor, Ian Macfarlane, found that too much transparency is harmful, apparently. He is said to be a "vocal critic" of releasing the minutes of Reserve Bank meetings and has been known to block FOI requests from newspapers.

Some research suggests there are instances where more information may cause speculation and hence greater market volatility. A recent empirical study (Bushee and Noe: 1999) indicates that firms with improvements in disclosure practices experience subsequent increases in their level of stock market volatility. They find that a policy of greater disclosure skews the composition of investors, toward those with a strong propensity to trade in the short run because they value it more than longer-term investors. The result of a greater prevalence of ‘fickle’ traders leads to greater volatility.

Second, even in cases where disclosure regulation is justified, the design of appropriate disclosure policies requires a careful weighing of the extent of disclosure.

This weighting should be sensitive to its costs and benefits. It should consider what information should be disclosed, who provides the information and verifies the quality, what are the enforcement requirements and so forth.

I'm a strong supporter of freedom of the press, but I have my criticisms of FOIA. I'll quickly cite two criticisms. First, anyone who has seen an agency's log of FOIA requests knows that FOIA is no longer used as a last resort. The Act is abused, and the costs are high (hence the reason Britain may introduce a fixed fee, unfortunately). Second, I haven't seen much empirical evidence against FOI laws pertaining to central banks. If such an absence exists, this represents a flaw.

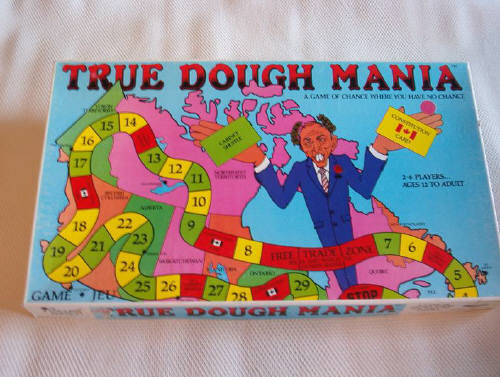

Still, FOIA is important and it is nearly as good as it could ever be, in Canada. Holding authorities accountable for their actions is crucial. As is the case with any institution, FOIA requests are denied if the central bank can prove that disclosure is damaging. As for irrelevant memos....they're unfortunately fair game. It's the cost of a greater benefit.

No comments:

Post a Comment